Were this a depression, the gap likely would have persisted. But as it was an outage — a suppression — the gap closed immediately, down almost 60% by the next quarter. By year-end 2021, the gap had effectively disappeared. Meanwhile, the government had continued piling on debt, such that Federal debt today is nearly $7 trillion, 30% of GDP, higher than it had been prior to the pandemic. This is a colossal amount of borrowing in a very short time. In an ordinary year, government borrowing might increase by 2-3% of GDP. The pace of debt accumulation from the start of the pandemic was almost an order of magnitude higher, representing the most radical increase in US borrowing in its peacetime history. This was a grand and perilous experiment in US fiscal policy.

Unsurprisingly, such debt-fueled stimulus led to a rapid and unsupportable increase in demand. Since the US economy could not produce sufficient goods to cover the stimulus, imports soared, leading to record trade deficits and bottlenecks at ports like Los Angeles and Long Beach. Inventories were stripped across the economy. New and used cars were scarce. Items normally available in demand, for example bicycles, became rationed, with retailers hoarding items like the spare parts necessary to run their maintenance operations. A flood of stimulus money blew up the supply chain.

With the stimulus winding down, this process has begun to reverse. Retailers like Wal-Mart and Target reported record increases in inventories in Q1 2022. Previously placed orders arrived just as the stimulus began to wear off. Where inventories had been scarce, suddenly retailers had too many goods in their warehouses. Mark-ups are being replaced by discounts. After the party of cash handouts to the public, the hangover is now on us.

On paper, the roll-off of the stimulus should lead to a technical recession with a decline of perhaps 4% of GDP. Accordingly, GDP declined by 1.6% in Q1 and a number of forecasters see negative growth in Q2 as well. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, for example, projects Q2 GDP growth at -1.2%. If expectations of decline prove correct, the first half of the year would qualify as a recession by the two negative quarters standard.

Such a technical recession need not cause high unemployment. With the end of World War II, US government spending collapsed, leading the economy to contract by 11% in 1945, but with almost no impact on employment. Brisk growth resumed the following year. If that precedent applies in the current case, growth might resume in the second half of 2022 as the effects of the stimulus wash through the system.

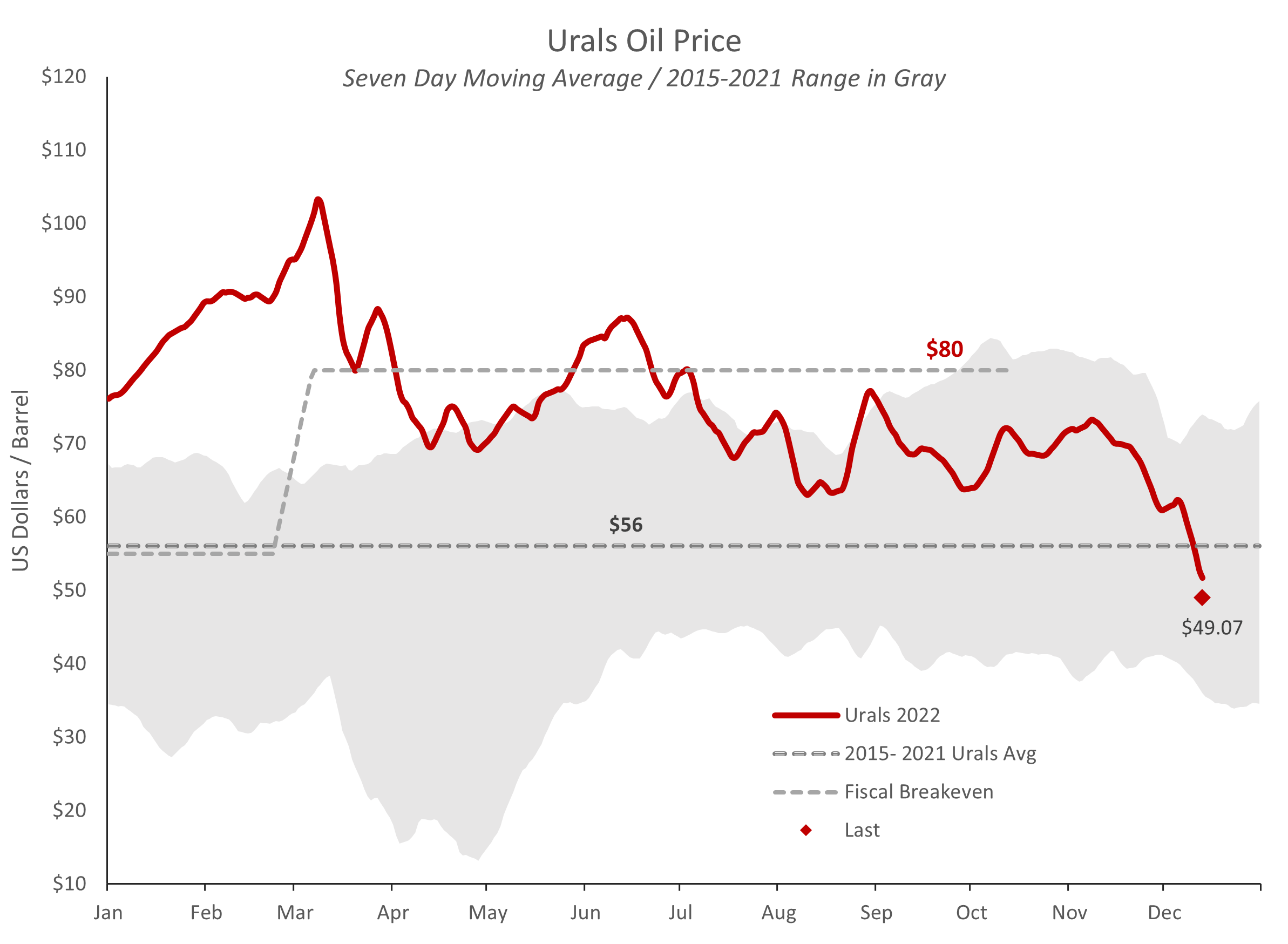

However, there are two complicating factors. The first of these is high oil prices and, even more notably, high gasoline and diesel prices. The last time the world saw such high prices, from 2011 to 2014, Europe slumped into a five quarter recession and the US struggled with ‘secular stagnation’. The story may be repeating itself now, with 55% percent of the US public believing that the country is in recession already, paired with consumer sentiment at its lowest level in seventy years. Both these polls reflect a public under considerable stress from inflation, most notably in energy prices. Ordinarily, such sentiment would be linked to looming recession.

High oil prices often occur in the context of rising interest rates, and this time is no different. As the Fed misdiagnosed the pandemic downturn, monetary policy was set far too loose, contributing to the worst inflation in forty years. As is typical in such cases, the Federal Reserve has started to raise interest rates to suppress the demand for money and thereby reduce inflation.

Not everyone believes the money supply and inflation are linked. In December 2021, Federal Reserve Bank chairman Jerome Powell told a House committee that the once-strong link between the money supply and inflation “ended about 40 years ago.” Powell’s beliefs rest upon the relationship of the money supply to inflation from the start of the Great Recession. From late 2007 until the start of the pandemic, M2 had risen by 60% more than GDP growth, and yet cumulative inflation over that 12 year period was only 20%. The Fed could print money with impunity, it seemed.

Standard economic theory, by contrast, attributes inflation principally to growth in the money supply. The Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman famously said that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” M2 is a widely used measure of the quantity of money, and it has increased by 39% since the start of the pandemic.

If Friedman were correct, we would expect prices to rise by the increase in M2 less the increase in GDP. GDP has risen by 5% since the beginning of the pandemic, and therefore we might expect prices to rise cumulatively by 34%, all other things equal.